Atelier Bow-Wow: How can we learn design through observing the everyday?

Introduction

Have you ever noticed people's everyday habits when using space? Perhaps the surrounding environment have become a natural part of your daily life. But if you observe closely, you may start to uncover unexpected spaces and even "hear" the stories they tell with their users.

Since I began studying architecture, I've found myself, almost unconsciously, observing the small, often overlooked details of city life during my free time. Through walking and photography, I've discovered interesting habits in the way people navigate their surroundings—some behaviors have even made me realize the subtle spaces and "furniture" hidden within the city. For instance, an elderly woman resting on a fire hydrant, an abandoned phone booth repurposed as a trash can, or a vendor at a rainy outdoor market building a temporary shelter with foam boxes...

Have you captured any fun moments of life in the city where you reside in?

Photographed by the author in Hong Kong, 2024.

Human behavior reflects the current needs and functions of urban spaces. Architecture is not merely about aesthetics; to design for people, one must first understand human behavior and habits. Rather than deciding the size and function of spaces from a bird’s-eye view, designers should try observing the everyday practices of local people. You might find that these habits of the locals contain more information to guide our designs than what’s initially expected.

Modernology (Kōgen-gaku)

In Japan, the practice of "street observation" can be traced back to 1923. It began with a painter and architect named Kon Wajiro. After the Great Kanto Earthquake, Kon decided to document everything he witnessed in the region. Through his records, he sought to understand how modern Tokyoites continued with their lives after the disaster.

From people's postures in daily activities, to the clothing they wore on the streets, and even the cracks on the dishes in budget diners, he rigorously sketched everything into his notebook.

On Human Posture and Eating Habits

Recorded by Kon Wajiro in Design and Disaster | Kon Wajiro

Kon Wajiro named his research “Modernology” (Kōgen-gaku). In his 1930 manifesto, “What is Modernology?”, he described how he scientifically and precisely documented the lifestyle of the Japanese people at the time. As recorded by anthropology professor Zhang Zhanhong, while both modernology and archaeology reconstruct the past through fragmented clues, modernology focuses more on the development of cities in post-modern Japan, the transformation of national life, and the rise and fall of traditions.

Ginza Fashion Survey,

Modernologio, 1925, Kon Wajiro

Ink on Paper

Wooden Houses,

Modernologio, 1925, Kon Wajiro

Ink on Paper

As technology advances, people's awareness of their surroundings seems to gradually diminish. We now prefer greeting friends on our phones over acknowledging those around us, and we opt to scroll through content online rather than sharing meals and conversations with family and friends. Yet, in this fast-paced, disorienting era, we need the spirit of modernology more than ever—to observe and understand the needs and culture of our time.

Street Observations

Inspired by modernology, Japanese artist Genpei Akasegawa, architectural historian Terunobu Fujimori, and illustrator Shinbo Minami founded the Street Observation Society in 1986. That same year, they published An Introduction to Street Observation. Through translation, this practice has since gained followers in other countries. Interest in "wild design" from everyday life has also begun to emerge in the architectural and artistic communities.

The Establishment of the Street Observation Society, 1986

In their book, Genpei Akasegawa and his colleagues recount their first encounter with the “pure staircases” in Tokyo in the 1970s—staircases that lead up and down but to nowhere else. This phenomenon is often a remnant of old buildings that have been repurposed. Akasegawa found these "useless" objects fascinating, believing they contained elements of “super-art.” During his time teaching at art school, he often led students onto the streets for fieldwork, examining everything from walls, utility poles, and manhole covers to small ads and road signs. To him, the abnormal states of everyday objects could be considered modern art.

Genpei Akasegawa Photographing Manhole Covers, 1986

At the beginning of An Introduction to Street Observation, Genpei Akasegawa describes his transformation from an artistic youth to an artistic adult, arguing that creativity should not be confined to “rectangular frames” but should instead “spread into everyday spaces.” This marked an important period when contemporary conceptual art began to break free from traditional boundaries and merge with daily life. From that moment on, Akasegawa started creating his art on the streets. His artistic philosophy mirrors that of Marcel Duchamp, as they both posed similar questions: “If everyday objects can become art simply by being placed in a museum and labeled as such, why can’t everyday objects outside the museum be art as well?”

Rojo Kansatsu Nyumon

An Introduction to Street Observation,

by Genpei Akasegawa, Terunobu Fujimori, and Shinbo Minami

This type of observational research has attracted and inspired many young architects and artists. In the architectural field, a studio called Atelier Bow-Wow was particularly influenced by the street observation studies discussed above, leading to some intriguing designs and research.

Atelier Bow-Wow

Atelier Bow-Wow is a small Japanese architecture firm founded by Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima. The two met at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and gained recognition by participating in architectural competitions. After graduating, they decided to start their own practice and established their research-based studio in Tokyo.

Founders of Atelier Bow-Wow

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Momoyo Kaijima

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto has a particular interest in vernacular architecture. He mentions how Architecture Without Architects introduced him to the idea that even non-architects can skillfully use local materials and building techniques to create remarkable structures. Momoyo Kaijima, on the other hand, enjoys observing human behavior and capturing these details through drawings. In recent years, as the Chair of Architectural Ethnography at ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), she frequently uses architectural drawings to document their discoveries through urban observation.

One of Atelier Bow-Wow's Projects in the Japanese Countryside (2018),

Satoyama Nagaya・Hoshinogawa ©Atelier Bow-Wow

"Made In Tokyo"

"Made in Tokyo" is a well-known handbook by Atelier Bow-Wow in the field of architecture. It also serves as a guide to help readers understand their perspective on Tokyo.

A tennis court surrounded by highways, a fusion of a shrine and an office building, a karaoke hotel... these "strange buildings" gradually emerged in the land-scarce contemporary Asian cities. What drives Tokyo to produce these so rapidly? This is a question that deeply intrigues me and is one of the themes explored in Made in Tokyo. If you've ever lived in similarly bustling and congested Asian cities like Shanghai, Hong Kong, or Tokyo, you might have encountered the kinds of peculiar and amusing urban spaces described in the book.

These are certainly not buildings that designers would typically consider "beautiful" (some might even say they're somewhat ugly), nor are they the usual subjects of architectural research. However, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto and Momoyo Kaijima believe that these "non-conforming buildings"* accurately reflect the lifestyle and needs of modern Tokyo residents. This prompted them to embark on a citywide search for "strange buildings" in Tokyo.

*Atelier Bow-Wow refers to these buildings that only puts emphasis on function and are forcefully inserted into the cityscape as "Da-me Architecture" (No-Good Architecture).

Atelier Bow-Wow's Two Famous Research Books

Left: Made in Tokyo,Right: Pet Architecture Guide Book

"We can detect what kind of troubles, ideas, or findings had made them create these buildings. The buildings tell us stories about daily lives and entire lives of the occupants. We want to build architectures which will become good partners with these buildings. One of the important roles of architects is to enlighten our society, but I think it is also important for architects to observe and find interesting ideas in whatever people are already doing and support them."

— Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Made in Tokyo 03: "Highway Department Store"

Describes the complex space where the architectural modules of the department store are merged with the highway.

(With the highway above and the shops below)

At the beginning of the book, Atelier Bow-Wow describes how, after returning from Europe, they began to question the city of Tokyo where they had once lived, feeling a stark contrast between Eastern and Western cities. If we take European countries like Italy or the UK as examples, even after modernization, they have retained architectural structures from several hundred years ago. In contrast, most buildings in Tokyo were constructed using modern technology over the past thirty to forty years. Gradually, the city has been taken over by towering skyscrapers and residential buildings.

The Differences Between the Streets and Architecture of London and Tokyo

With the rapid economic development of Tokyo, the demand for buildings has steadily increased. Gradually, many unusual composite buildings, with unconventional uses or structures, began to appear in the city. Atelier Bow-Wow collected photos of these "odd buildings," printed them on clothing, and turned them into merchandise as part of an architecture exhibition. Later, as they noticed more of these buildings popping up across the city, they began giving each one humorous names to enhance people's impressions of urban spaces in Tokyo. By 2001, they decided to compile them into a guidebook, which became Made in Tokyo. Even today, the project continues.

Made in Tokyo 20: "Advertisement Apartment"

Describes a giant billboard placed above a residential building, designed to be visible to airplane passengers. This reminded me of Venturi's discussion in Learning from Las Vegas about the importance of billboards as a way to communicate with modern people.

Personally, I love Made in Tokyo, and I think it's an excellent introduction to architectural theory for beginners. Among more than 100 "odd buildings," Atelier Bow-Wow carefully classifies them by appearance, use, and overall structure. I believe these non-architectural forms often arise from spatial limitations and a prioritization of practicality. Thanks to the "odd buildings" in this handbook, we can truly witness the full picture of Tokyo, understand what separates architecture from non-architecture, and see the various ways buildings can accommodate multiple functions.

Pet Architecture

During the time Tsukamoto Yoshiharu and his team were working on Made in Tokyo, they also rediscovered the tiny hidden spaces in Tokyo. They gave these small spaces a cute name: "Pet Architecture."

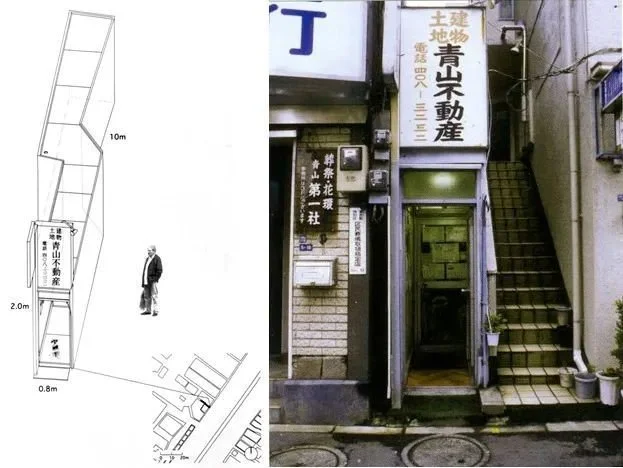

When the book was first published, the only example included was Pet Architecture 001, a tiny real estate shop. It had a narrow 0.8-meter path that could only fit people walking in single file (and likely in only one direction). This small space, awkward and amusing, reflects both the issues with Tokyo's urban planning and the mindset of its people. When confronted with unused small spaces, people think, "What a waste," and as a result, these quirky mini-buildings pop up, hiding in the city's corners and seeming almost unbelievable.

Pet Architecture 001 is an extremely small real estate shop.

In highly dense cities like Tokyo, even a small alleyway or a gap between buildings can give rise to architecture. Although "pet architecture" isn’t the type of space where people can comfortably stretch out their legs, it may serve as an example that inspires architects’ imaginations for small spaces. We can envision the relationship and collision between architectural functions and urban spaces, thus creating unprecedented buildings.

Observation → Design

Atelier Bow-Wow's research revolves around the theme of Architectural Behaviorology. They aim to observe people's behaviors and extract insights from them to optimize the spaces that foster these behaviors. This type of research has led them to rediscover the unique environments surrounding each building, highlighting the organic nature of architecture (which does not necessarily prioritize function like modernism).

"Human behavior is the best resource for design." — Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Mini Public Spaces

Inspired by Tokyo's architecture, Atelier Bow-Wow's own "pet architecture" works often operate on a magical scale, combining observed elements to create new spaces. For example, in their White Car Mobile Stall project in 2002, they incorporated local food, culture, and transportation to create a mobile architecture that suited the local context.

White Limousine Yatai, 2002, Credit: Atelier Bow-Wow

A yatai is a common type of mobile food stall in Japan (I often saw them in Fukuoka). People gather under the lights to enjoy warm food, drink sake, and engage in lively conversations, creating a very warm and joyful urban experience.

Image credit: Peikie for Fukuoka’s yatai.

In the snow-prone city of Tokamachi, Atelier Bow-Wow chose to use white to express the architectural concept of their yatai mobile food stall. During its first use, they carefully prepared white foods, such as local tofu and radish, to match the aesthetic of the structure. Once again, they transformed space into a playful act of performance art, blending architecture and local culture into a unique, interactive experience.

The White Limousine Yatai is a mobile, multi-person food cart designed by Atelier Bow-Wow. It creatively merges architecture, local food culture, and mobility into one cohesive, portable dining experience.

Credit: Atelier Bow-Wow.

Art Exhibitions

After Made in Tokyo received praise from the architectural and art communities, Atelier Bow-Wow was invited by exhibition organizers worldwide to design unique "Pet Architecture" for local art museums. Initially, they found it challenging to replicate the serendipitous nature of these small structures. However, through their travels, they discovered that people in different cities showcased unique forms of entertainment in public spaces. The most fascinating aspect was how people's behaviors often made use of local tools and objects in creative ways.

On the busy streets of Shanghai, bicycles are used not only to carry people but also various goods of all sizes.

During their visit to Shanghai, Atelier Bow-Wow observed a fascinating sight: bicycles weaving through busy streets, bustling alleyways filled with multi-generational families, and elderly people playing chess and drinking tea in the parks. However, with Shanghai’s rapid urbanization, many of these daily scenes have gradually faded, and old buildings are increasingly being marked for demolition.

In response, Takamoto and Beida began to experiment by combining observed behaviors and spatial elements to create a new form of mini architecture and furniture. They integrated bicycles with items such as tables, chairs, and single beds, evolving their concept of "Furnicycle" into various innovative forms.

"In Shanghai's streets and art museum exhibitions, Atelier Bow-Wow's 'Furnicycle”

‘Furnicycle’ has attracted the attention and use of passersby on the streets of Shanghai.

Designs like the ‘Furnicycle,’ which act as social experiments, are quite rare. They cleverly prompt people to rethink their relationships with culture, cities, and objects. When viewing this piece, it’s worth stepping away from a purely practical perspective. Instead, applying Atelier Bow-Wow’s approach of behavioral and ethnographic analysis highlights its cultural value.

Their exhibitions achieve global success because they recognize the unique behaviors and cultural highlights of each city and emphasize these features in their work.

House & Atelier Bow-Wow

Even in their own house and studio, Atelier Bow-Wow’s designs are centered around behavior. By using sectional views, they help non-designers understand the relationship between a building’s interior and exterior, and the behaviors of its occupants."

House and Atelier Bow-Wow, Studio and Residence Combined

Their home is not only the culmination of their research into living spaces but also a space that shapes their ideal lifestyle. The couple often cooks in the kitchen and shares meals with people from the studio. They believe that, beyond just space, food and various items can also create wonderful living memories between people.

House and Atelier Bow-Wow The Relationship Between the Studio Library and the Kitchen

Reflection and Conclusion

"If local residents understand their own living needs better than architects and can create their own buildings, is there still a need for architects?" This question sparked a series of debates during my university years. However, after exploring Atelier Bow-Wow's research, I've come to appreciate the significance of architects and the inspiration that our surroundings can provide.

Cities are always diverse and constantly changing. Instead of creating a new architectural language and hoping it lasts forever, it is more valuable to design buildings that embody the spirit of local architecture, singing the identity of the land. By learning to use your eyes to discover the diverse forms of people and spaces around you, you deepen your understanding of both the world and yourself.”

About the Author

Xiaoyu (shortened to Yu) currently resides in Canada, experiencing moments of excitement and confusion in the architectural field. She enjoys reading and analyzing the stories and theories behind various designs. After graduating with a degree in architecture, she hopes to share her own stories with others to explore her interests and the meaning of design.

Related Books

Translator : J